On February 25, 2020, The Commercial Appeal of Memphis, TN published an article with the title, “How 3 Memphis companies are making diversity and inclusion a priority”. My immediate response was “Where is the E?” What happened to “equity”?

The article highlights 3 black executives of the some of the largest companies in Memphis: FedEx, First Horizon National Bank, and International Paper.

Just 2 days prior, FedEx announced its first black head of an operating company, who is also a woman.

While there is much to celebrate in these stories, and we certainly should congratulate those highlighted for their accomplishments, I am curious about two things: Why was equity, which is now ubiquitous thanks in part to the easy-to-use DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) acronym, absent from this story? And what might that say about equity within those corporations?

I can offer all sorts of conjecture about why the author didn’t address equity. I’ll pass on that. I did a little digging to get into the second question though.

As someone who is slightly obsessed with governance, I visited each company’s website and perused their Boards of Directors listing. It was fascinating. But before I get to what I found, let’s talk definitions.

In terms of race and ethnicity, diversity is when you have racial and ethnic representation from various groups within your ranks. Having “one of each” is not diversity. A single person cannot be diverse. The word implies multiples.

Here’s a twist though: allied diversity. Simple representation gives the cosmetic appearance of racial diversity, but it does not ensure the interests of the group. It is entirely possible to have black people in leadership who are anti-black; or Latinx people who are anti-Latinx. Any type of racial diversity can benefit your organization, but allied racial diversity can benefit the people of color within your organization and perhaps the people of color affected by your organization. This does not mean people of color are the only people responsible for the well-being of employees and constituents of color.

Inclusion could be defined by whether people of color feel they are able to take full advantage of the privileges of membership in your organization. If they feel their race or ethnicity limits their access or opportunity in anyway, your company is not inclusive.

Race equity is when an organization’s impact internally and externally is distributed without racial disparity. Where FedEx, First Horizon, and International Paper are concerned, this would translate into issues of wages and impacts on the communities in which they operate. (Of course, there are all sorts of issues of intersectionality to address as well, but this isn’t a master class. For more on that see what Beloved Community has to say as a start.)

Can a company successfully pursue equity without racial and ethnic diversity or inclusion on its governing board?

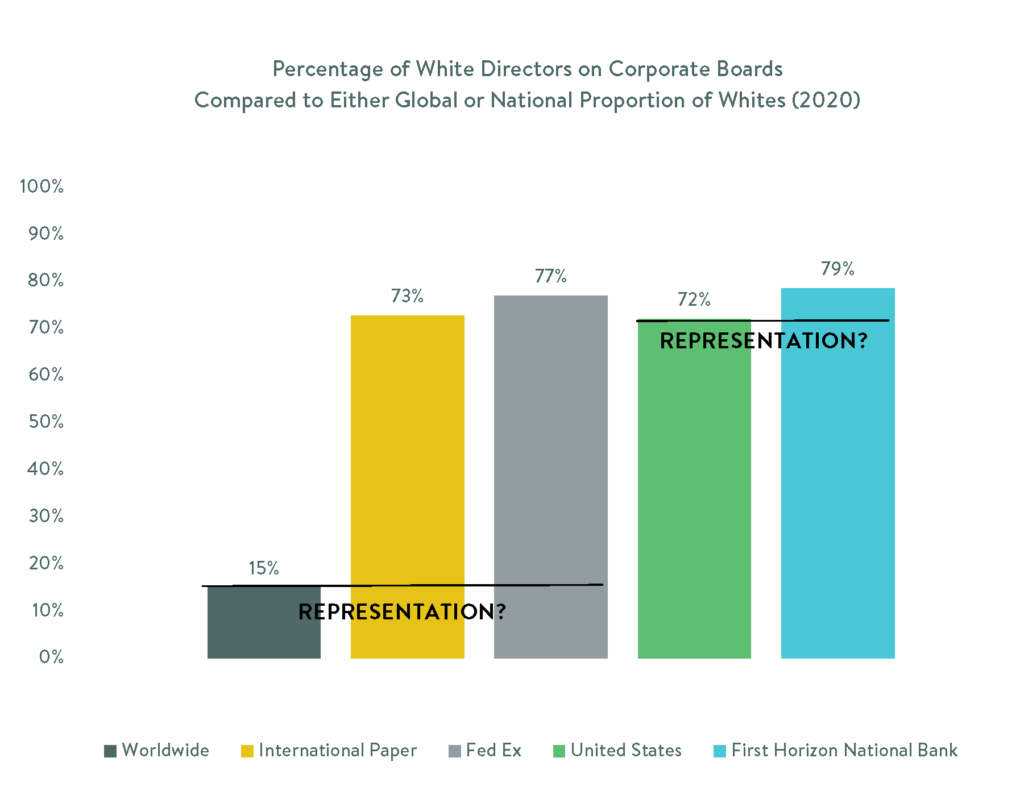

A brief review of the boards of directors of FedEx, First Horizon National Bank, and International Paper revealed there is a highly disproportionate representation of white people on the boards of FedEx and International Paper, if the global population is the comparison, and only a slightly disproportionate number of white people on the First Horizon board because I used the entire U.S. population instead of limiting the count to the states where the bank operates. (They have recently undergone a merger here and an acquisition there, so their identity isn’t entirely clear. First Horizon was also incredibly difficult to manage because they do not have photographs of their board on their website.) I would be curious to know how representation might change if the employee population were the comparison.

Why do boards of directors matter? They set expectations for the chief executive and hold them accountable to meeting those expectations. Who expects equity?

In general, the board makes decisions on shareholders’ behalf and has a legal duty to act solely on their behalf. The board looks out for the financial well-being of the company. Such issues that fall under a board’s purview include the hiring and firing of executives, stock dividend policies, and executive compensation. In addition to those duties, a board of directors is responsible for helping a corporation set broad goals, support executives in their duties, while also ensuring the company has adequate resources at its disposal and that those resources are managed well.

Jill Griffin, Forbes

Corporations are not likely to be beacons of justice. The profit motive at the heart of capitalism mitigates against humanity. If they are going to promote themselves, or allow themselves to be promoted, as attending to issues of racial inequality it might be worth digging a little deeper into what that really means for every level of the organization.

For a PDF presentation on corporate board duties and liabilities from the Stanford Graduate School of Business click here.