Something about results-based work and continuous improvement practice has always made me a little uncomfortable. Part of me finds measurement, tracking, and accountability appealing. Another part of me feels uneasy about the beliefs and culture in which those practices are rooted.

If anyone deserves results in the U.S., it’s indigenous folk and people of color. We have all been on the receiving end of the worst this country has to offer. Yet we are here, so we can and should benefit from the best. Getting from where we are on every social outcome measure to where equity says we should be will require deliberate effort and accountability. Internal accountability. External accountability. Shared accountability. Accountability to us. Accountability for our outcomes.

Results matter for us.

I am a devotee of results-based accountability (RBA) and continuous improvement processes. They are transparent and understandable. The appropriate use of data can leave no place for governmental and organizational leaders to hide, which is likely why they aren’t in use everywhere. To implement RBA, one must be prepared to be honest about what their work is producing. As Mark Friedman’s book on the topic says, “Trying hard is not good enough.” Or as a worlds-famous results guru says, “Do or do not. There is no try.”

That said, when one “does not”, it’s useful to know why and make a plan to “do” again. Continuous improvement processes help us to fail forward with intentionality. Once we know what to do when we fail, we can immediately design and shift to the next action plan.

How could either of these things be a problem? Why have I wrestled with them the way I did in Sunday school, where I occasionally got kicked out of class? Something has just felt off. I’ve never been a good devotee.

I’ve studied, written, and talked about race for decades. Digging into ideas and concepts and rooting out the oppression within is fun for me. I had a blind spot where RBA and continuous improvement were concerned, but is was small enough for me to sense I needed to look more closely.

When a friend pointed me to Jones and Okun’s the characteristics of white supremacy culture from Dismantling Racism: A Workbook for Social Change Groups, it was a code-breaking moment. I could see everything I sensed was there.

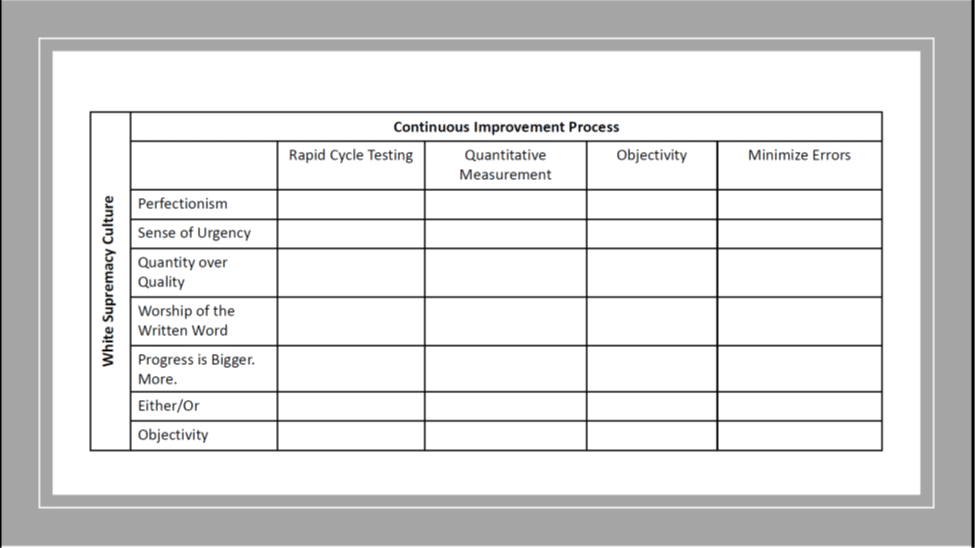

Characteristics like sense of urgency, quantity over quality, progress is bigger and more, and objectivity (a concept that plagued me in graduate school) describe white supremacy culture but could easily describe continuous improvement.

The roots of results-based work and continuous improvement are in finance and manufacturing. Total Quality Management. Plan-Do-Study-Act. Six Sigma. Although RBA has more human language and clearly comes from a place of concern for humans, especially around “better off” measures, the practice of setting targets, monitoring trends, and producing things makes objects of humans. It can be dehumanizing to engage in conversations about better, faster, and more when talking about education, health, and crime. It is even more likely to be dehumanizing when the people whose lives are deeply and negatively impacted by those systems are absent from planning, accountability, and continuous improvement conversations.

It is a tricky proposition to use tools with these kinds of origins in the pursuit of justice. But that widely misused Audre Lorde quote about the master’s tools and the master’s house [PDF] does not have to apply here.

Three practices can keep us on the right path:

- Be empathetic. Every social problem over which we toil has human beings at the center. What are their lives like? What have their experiences taught them? What expertise has that produced? How dehumanizing must it feel to watch people define your life’s challenges and create solutions without a single effort to talk with you?

- Be respectful. There is value in all types of knowledge. I am equally proud of the knowledge I gained from growing up in a home with very limited resources as I am of that which I gained from elite schooling. I also know that my childhood life is a distant past, which requires that I respect the knowledge of those currently experiencing poverty and many other social and economic challenges.

- Be kind. This should probably be “check yourself before you wreck yourself” but that doesn’t fit the tone of this piece. I have witnessed far too many exchanges where “community leaders” are so determined to assert their power and clarify their vaunted position that they lack the self-awareness to see the ways in which they are being cruel. Cruel in their assumptions, dismissive in their tone, and demeaning in the “solutions” they put forth.

Those of use who are trained in RBA and continuous improvement practice are best positioned to ensure the culture of this work doesn’t perpetuate white supremacy. The way we engage in training and implementation determines how the work and the culture will be propagated.